Iso Rae, the Unrecognised War Artist

In early 1914 the town of Etaples in Northern France was home to a colony of artists, a predominantly anglophone group of painters noted for a style that incorporated realist subjects and impressionist light. This all changed following the outbreak of the First World War. Etaples was transformed into the British Army's largest base camp and its artists dispersed, with some entering service and others seeking refuge in Britain.

But one artist who remained in Etaples was Iso (Isobel) Rae, a 54 year old painter from Melbourne, Australia. She had lived in the town since 1890 with her mother and sister, Alison, exhibiting her art at the Paris Salon. Owing to her mother's frail health, Rae decided that the journey back to Australia in 1914 would have been impossible and instead set about making her own contribution to the imperial war effort by enlisting in the Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD).

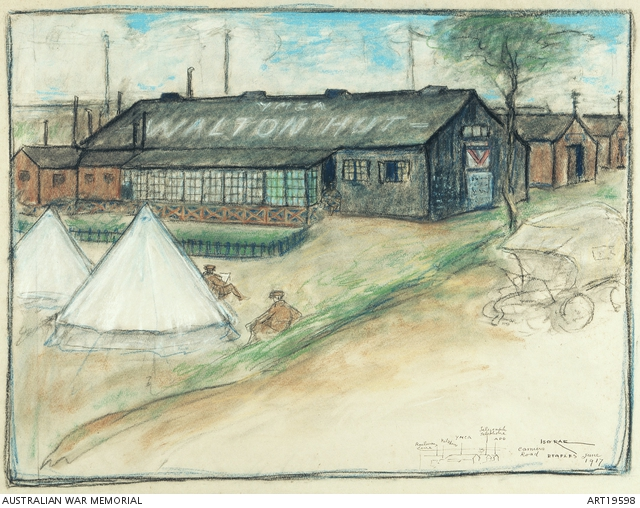

She remained in Etaples for the duration of the war, continuing to create art alongside her war work. By 1918 she had produced 200 drawings of the Etaples camps, documenting the lived experience of a place dedicated to training, waiting, and healing. Through her work, which was dominated by simplistic shapes and dark lighting, we get a real sense of the atmosphere of the place, as somewhere heavy and uncomfortable. Alexandra Walton of the Imperial War Museum recorded an audio essay about Rae for BBC Radio 3 in 2018, in which she highlighted the prevalence of night scenes and the lack of faces featured by Rae, which contribute to her sense of the mundane and the everyday, rather than reflecting specific moments.

Rae was placed by the VAD to work for the YMCA, who ran 33 recreation huts in Etaples. Unfortunately, it doesn't appear that any written accounts of her war work exist, but we can tell a lot about what she did from what she chose to depict, with the Red Triangle emblem of the huts prevalent in her images. It seems, for example, that the YMCA cinema was at least part of her responsibilities. The only known photograph of her from the camp is taken outside of the cinema office, with Rae seated alongside a group of soldiers.

The cinema is also the focus of one of her most famous paintings, 'Cinema Queue', now owned by the Australian War Memorial (AWM). Art historian Catherine Speck has described how 'the glow of light from the cinema office appears as a symbolic relief in a war which was at a stalemated mid-point'. The crowd of men waiting to enter the cinema depicted in the piece is common in descriptions of the YMCA's cinemas, and as Speck identifies, this was seen as many to be a relief, or an escape from the realities of war. Rae wonderfully and simply illustrates this as the cinema's glow lights up the silhouettes of the entering men.

Another series of images also have a glowing light at their centre. The so-called 'A Devil' charcoals depict a mixed group of soldiers standing around a fire pit, enjoying an informal conversation. Not only do these echo the ideas of finding the light amid the dark, but they also show the way soldiers would mingle while in the camp. The image below right includes a man in hospital blues. a British soldier, a New Zealander and a Scotsman, each of different regiments socialising together in camp. They suggest an informality to life at Etaples and represent that mixing of people from different nations and backgrounds that was unique to military life.

Despite being a prolific artist throughout the First World War, Rae was not among the 17 official war artists appointed by the Australian War Art Scheme and nor was Jessie Traill, a fellow artist and VAD worker stationed at Rouen. Charles Bean, who went on to become the Australian Imperial Force's (AIF) official historian, oversaw the commissions to the Australian war art scheme and described his ideal candidates as 'enthusiastic young men doing their best to help their country's record'. Clearly Rae and Traill did not fit with this vision and no women were appointed official artists in the Australian scheme during the war, even while women such as Anna Airy were given commissions elsewhere.

Speck highlights Bean's argument in her study, stating that 'women's representation of the landscape was deemed less authentic than that portrayed by the official male artists'. This is difficult to reconcile with the atmospheric works created by Rae, and suggests the complete disinterest of Bean and others to including women, in what they considered a man's role. But there were also logistical reasons that complicated the appointment of women. The male artists were given commissions through the AIF and were therefore considered members of the military. This service was not open to women, creating an administrative barrier which the already disinterested officials did not wish to readdress.

However, Rae's exclusion from the official war art scheme may have run further than just her gender. Bean disliked modern art and referred to many styles as 'freak art', preferring instead art that was more classic. Rae's art may well have fallen into this disliked category, and coupled with the fact it depicts life behind the lines and not at the front, Bean could have considered it insignificant in the portrayal of Australia's war. Unfortunately, it doesn't appear that there are any surviving records that cover whether there had been any discussions surrounding Rae and Traill's potential inclusion in the war art scheme, so this remains speculation.

Fortunately, after the war Bean's Australian War Memorial acquired many pieces of Rae's art. They are, as Speck, Walton and others have recognised, important elements in our remembrance of the First World War, as a conflict not only of active fighting, but also of immense organisation and logistics, of training soldiers and housing them in vast spontaneous towns, of entertaining them, and of healing their broken bodies.

Rae gives us a unique insight into life at the Etaples base camp. She shows us how the camps were arranged, how the soldiers would move through them and use the spaces, and the scale of the organisation. Pocket cameras were rare during the war, especially after they were banned by military authorities, and so there are few photographs of camp life. And even where those do exist, their grainy black and white nature means they are unable to communicate the atmosphere and mood of the camp in the way that Rae was able to in her art. More than just sketched recordings of what she witnessed, her work is a legacy of the experience of war that in turn aids our modern understanding.

Kathryn

https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/m00011hs

Snowden, Betty (1999). "Iso Rae in Étaples: another perspective of war"

https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/art_australia

No comments: