'Set Somewhere in the Quiet Isles': The Tolkien Film & the Poetry of Geoffrey Bache Smith

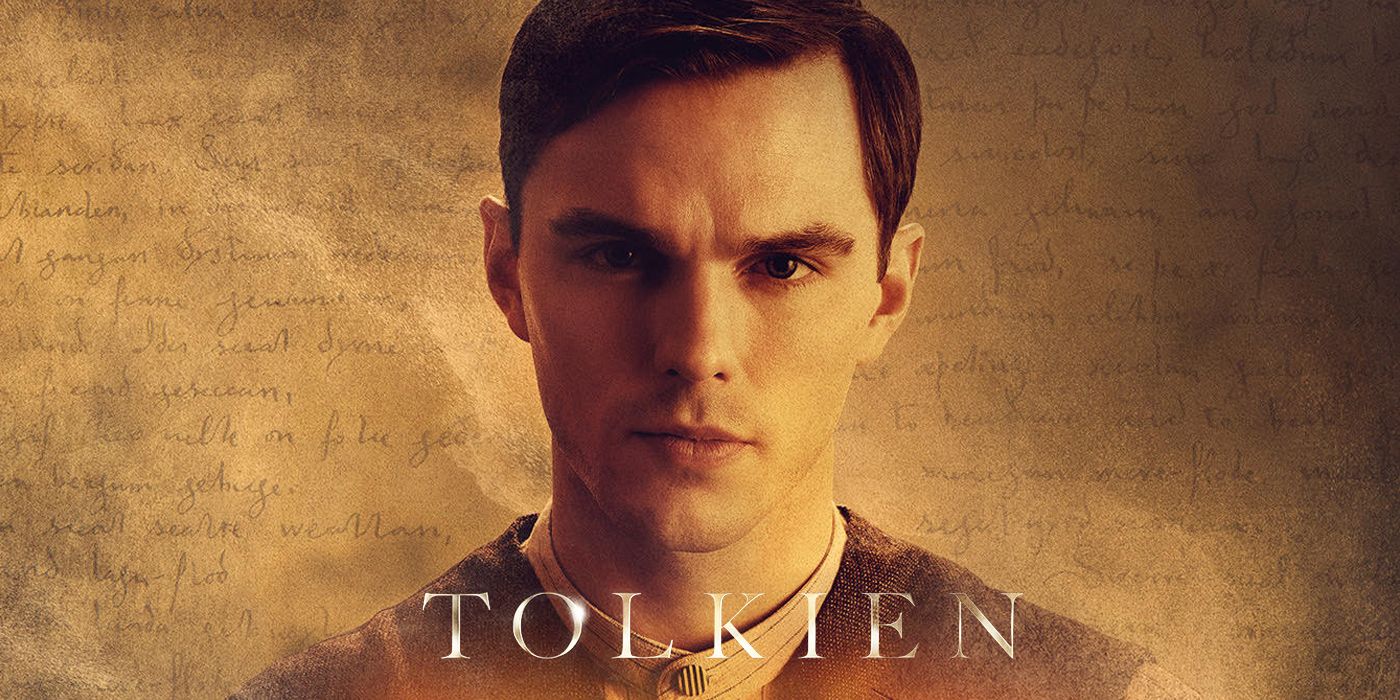

I have to confess, I'm not a Lord of the Rings fan. I read The Hobbit many years ago, but was didn't really enjoy it, despite JRR Tolkien's rich and complex world. Nonetheless, I remain an admirer of Tolkien as a great writer and thinker, so when I heard about the new biopic Tolkien and the fact it covered his military service during the First World War, I wanted to see it. Plus, there was a little cameo from one of our college's quads which I wanted to see.

I went into the film with an open mind, wanting to see Tolkien's life at Oxford and his experience in the First World War, but not expecting historical accuracy. Usually for films like this I can suspend my expectation of truth just to enjoy the film for what it is. The Imitation Game remains one of my favourite films despite its inaccuracies, and others like My Boy Jack and Journey's End do well to present the war while playing to the appeal of cinema.

However, I couldn't get on board with Tolkien's war. Of course it was the expected muddy and bloody tropes, but just what were Tolkien and his batman, Sam, doing in the front line and going over the top in search of a friend? Why weren't they with their own battalion?!

Despite this, I did enjoy the film overall, if a little more for its Oxford content than its war scenes. I liked the story of friendship between the four members of the TCBS (Tea Club & Barrovian Society) and the way they developed from their school days to early adulthood.

When I came home, like the true history dork I am, I was keen to know more about Tolkien's dear friends, especially Geoffrey Bache Smith, who the film lingered on longest. The anthology of poems written by Smith discussed by the cinematic Tolkien can be read online and are a good collection of rhymes about the worldview of a man in his early twenties. I looked to the section of his war poems with particular interest.

The poems written by Smith during the first few years of the war are largely preoccupied with thoughts of death; a sad premonition given his premature death from wounds at Warlincourt in December 1916. His perception of the world was clearly and deeply affected by the death he witnessed at war: 'We who have seen Death surging like a flood, Wave upon wave, that leaped and raced and broke'. Dying was continually on Smith's mind, at least in the influence on his writing, and not dissimilar from the piles of bodies that haunted Tolkien in the film. (Were those bodies really there, or were they illustrations of the fear of death in their minds?)

Yet, unlike some of the "celebrities" of war poetry, there is less about the bloodiness of war and more about religion. Smith's religion evidently shaped his understand of life and the war and throughout his poems is intrinsically tied to his conception of death.

The poem 'Intercessional' is a particular example of this:

There is a place where voices

Of great guns do not come,

Where rifle, mine, and mortar

For evermore are dumb:

Where there is only silence,

And peace eternal and rest,

Set somewhere in the quiet isles

Beyond Death’s starry West.

O God, the God of battles,

To us who intercede,

Give only strength to follow

Until there’s no more need,

And grant us at that ending

Of the unkindly quest

To come unto the quiet isles

Beyond Death’s starry West.

Of interest here is his use of the term 'God of battles', which I first encountered in Stuart Bell's book Faith in Conflict on religion in the First World War. Bell has identified the widespread usage of this term in the First World War, which was taken from the Old Testament to describe a presentation of God as presiding over war using it to aid the righteous army. Smith's use of the phrase is not uncommon and is similar to some of Rudyard Kipling's poetry published in 1896.

However, Bell has also argued that there was increasing tension over the use of the 'God of battles' during the First World War, quoting EG Miles writing for the YMCA as saying 'it is getting more difficult every day to reconcile the God of love with the God of battles'. However, Bell concludes that this stance was not widely adopted by the church at the time, and it certainly does not appear to have troubled Smith.

The poem 'Intercessional' reads as a prayer. It is a prayer for God's strength and support not only in battle, but also in death, the inevitability of which Smith has accepted. This commitment to God and his appeal for support fits into a narrative of imperial Christianity which Smith would have been influence with during his private school education at King Edward's in Birmingham.

I think it's one of the strengths of the Tolkien film that it shows the development of the four TCBS boys from precocious teenagers to military men and the influence their schooling had on their lives. Its motivation was evidently to show the origins of the great mind behind The Lord of the Rings, yet it also, for me at least, gave a window into the influences of the First World War generation through the friends of the TCBS. Without it, I don't think I would have given a thought to the poetry of Geoffrey Bache Smith.

And as for my verdict on the film overall? It's certainly worth a watch, but maybe wait until it's inevitably on Netflix next year.

Kathryn

No comments: