Huts by Name, but not by Nature

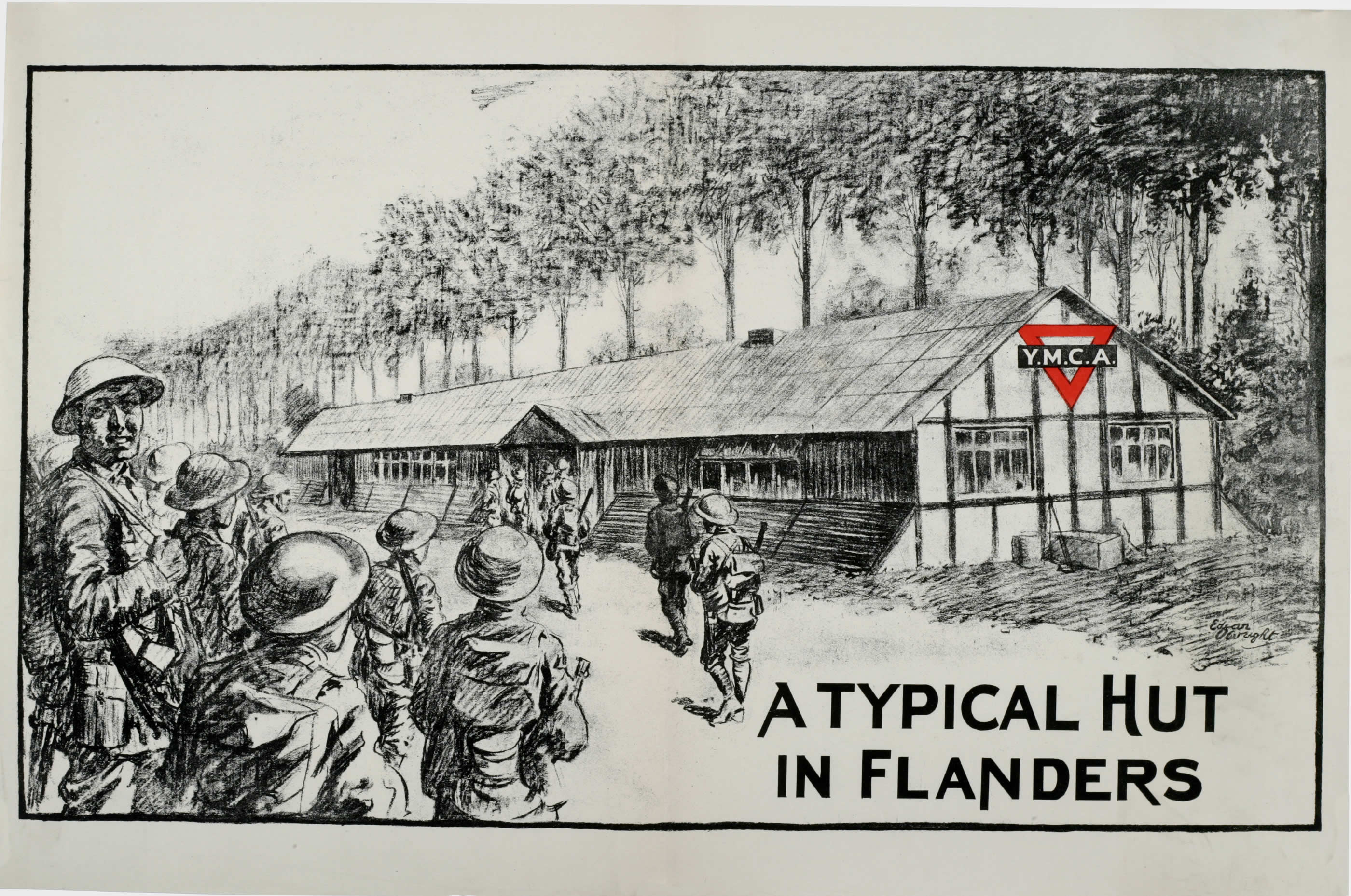

The war work of the YMCA and similar associations (Church Army, Salvation Army, etc) quickly became known as "hutwork". The reasoning for this is simple: the vast majority of the sites were temporary wooden huts, which could provide a space for recreation, refreshments and religion wherever one was needed across the active fronts. These huts were a ubiquitous sight in the early Twentieth Century military. They provided barracks and hospitals: the large base camps, such as Etaples, became hutted cities.

'Hut Week' became a popular advertising tool for raising funds to power their war work. In press articles about the YMCA, particularly those aimed at the Home Front, the 'hut' became the central image of their work, the imagined home for soldiers between duty. Costing roughly £500 per hut, communities hosted hut drives to fundraise for a flat-pack hut to be sent to the Western Front, as the simple buildings came to capture the imagination of what the YMCA did.

'Hut Week' became a popular advertising tool for raising funds to power their war work. In press articles about the YMCA, particularly those aimed at the Home Front, the 'hut' became the central image of their work, the imagined home for soldiers between duty. Costing roughly £500 per hut, communities hosted hut drives to fundraise for a flat-pack hut to be sent to the Western Front, as the simple buildings came to capture the imagination of what the YMCA did.There is no data (that I am aware of) for how many huts were built and used by the YMCA during the First World War. Similarly, there is no comprehensive list of all the different structures and locations that were used for so-called 'hutwork' by the Association. In many cases it was not practical or even possible for the YMCA to establish a wooden hut at every location where one was needed, particularly in more transient phases of the war. As a result, all manner of buildings and structures came to be used by the YMCA. This article takes a look at just some of them.

Tents and marquees were some of the most common substitutes for huts, particularly in the temporary camps. The interior space was largely the same as that of the hut, albeit without windows (not that, often, there was much to look out on). This was a more flexible space, that could be put up and taken down much easier than a wooden hut, but that still provided a large space in which troops could gather with protection from the outside elements.

Tents and marquees were some of the most common substitutes for huts, particularly in the temporary camps. The interior space was largely the same as that of the hut, albeit without windows (not that, often, there was much to look out on). This was a more flexible space, that could be put up and taken down much easier than a wooden hut, but that still provided a large space in which troops could gather with protection from the outside elements.As early as August 1914 the Rev. Canon Walter Hicks was commending the 'YMCA tent' which 'encouraged those ... to keep pure, clean and straight'. The tent could be quickly established as and when required. In 1918 the Evangelist Gipsy Smith estimated that there were 80 marquees following the army up and down the 'firing line', although in reality it was rare for a marquee to get too close to the front line.

The tent was also easier to transport to the Eastern Fronts. This image is from the YMCA in Baghdad during the Mesopotamian Campaign. A canvas tent could be shipped to the Middle East and was much easier transported once it was there. Unlike on the Western Front, there were also fewer concerns about keeping the hut warm. Shade would have often been the priority for the soldier when looking for a recreational space, which the tent provided.

The tent was also easier to transport to the Eastern Fronts. This image is from the YMCA in Baghdad during the Mesopotamian Campaign. A canvas tent could be shipped to the Middle East and was much easier transported once it was there. Unlike on the Western Front, there were also fewer concerns about keeping the hut warm. Shade would have often been the priority for the soldier when looking for a recreational space, which the tent provided.

In more permanent settings, buildings were requisitioned, such as this school in Armentieres (above, left). You can just about see the Red Triangle emblem on the front gate. Some buildings were more luxurious than others. This 'hut' house in Kemmel (1917; above, right) was somewhat draftier, used despite its collapsing roof. With resources limited, it made sense for the YMCA to requisition buildings where it could.

Arriving in Peronne on Good Friday 1917, YMCA regional co-ordinator Barclay Baron chose the 'ruined theatre' for use as a YMCA hut, a particularly spacious venue, in addition to 'requisitioning the schoolroom for our use and a house suitable for the billeting of our small staff'. He described the warm reception with which the Association was welcomed in the city, particularly from the Town Major who allowed them to take over any buildings they wished.

Closer to the front lines, dugouts were particularly useful, providing shelter and security from artillery fire. In drawings and postcards depicting the YMCA's work, these sandbagged burrows are probably second-most common, behind the wooden hut.

One dugout located on the infamous Kemmelberg was occupied until the very last. During the German Spring Offensive in 1918, the YMCA workers remained at their posts right up until the retreat of the British forces.

Similarly, basements provided a secure hut environment near to the action. This basement hut (right; source) was in the building that is now College Ieper, facing the ramparts on the eastern side of Ypres. This photo was most likely taken in the summer of 1916 and with the majority of the city's buildings destroyed, basements remained a safe haven for the institutions attached to army life.

Similarly, basements provided a secure hut environment near to the action. This basement hut (right; source) was in the building that is now College Ieper, facing the ramparts on the eastern side of Ypres. This photo was most likely taken in the summer of 1916 and with the majority of the city's buildings destroyed, basements remained a safe haven for the institutions attached to army life.

Another YMCA centre in Ypres was located in a cellar below the Lille Gate at the southern edge of the city. This sketch is most likely of this 'hut', which was run by Dr CJ Magrath. Baron, who visited many huts across the Western Front, described it as 'an unusual YMCA' in which you 'went down by narrow steps to the tiny canteen where men chatted and smoked and drank tea elbow to elbow.'

The YMCA made use of any venue it could to provide soldiers with the comfort, entertainment, and solace they needed on active duty. By transporting, requisitioning and building hut-like facilities wherever it could, the Association was able to offer the best provision possible to support the Army. Although it was hutwork in name, many of the YMCA establishments were temporary and makeshift, as was so often the necessity of war. For the soldiers frequenting the Red Triangle, it was what lay inside that mattered.

Kathryn

All images are from the Imperial War Museum's Archive unless otherwise stated.

This article is a great resource. I found the tips you mentioned to be very practical and easy to implement. Thanks for the valuable advice.

ReplyDeletewooden world map for wall