The YMCA at Etaples

For many soldiers, the base camp at Etaples was their first place of settlement upon arrival in France. Having arrived into one of the Channel ports and spent up to a few days in a neighbouring camp, battalions of soldiers would then be sent by train to one of the base camps for further training before their deployment to the front line. Etaples was the biggest of such camps, with over one million men being said to have passed through Etaples between 1915 and 1917, although it operated throughout the war. One such soldier, George Culpitt of the Royal Welch Fusiliers, described arriving at the 'small station' before entering the 'very large' Etaples camp on his second day in France in 1916. He spent a few weeks there with 10th battalion, before they were dispatched to the trenches.

Such time in training was often very dull, and so huts like those provided by the Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA) were important centres for the entertainment and recreation of the men. To keep up with their demand, the YMCA had more than 33 huts (as recorded in 1916), stationed around the various training camps which together constituted the Etaples base. There were also huts provided by other agencies and the soldiers did not always differentiate between them. Culpitt referred in his diary to visiting 'the YMCA Church Army Hut', despite the YMCA and the Church Army being two different organisations. Although both organisations provided huts and were motivated by Christian morality, the Church Army was run by the Church of England, whereas the YMCA was an independent, nondenominational charity. Arthur Keysall Yapp, National Secretary of the YMCA, saw these huts to be a crucial part in men contracting the "Hut habit", of routinely visiting and relying on the YMCA for comfort, in the hopes that it would become part of the soldierly routine once the men reached the front.

Thomas Winter was among the YMCA's workers based at the camp. He wrote of the huts' provisions which exceeded the regular provision of refreshments and light entertainment to include concerts, lectures, weekly Bible study and free French lessons; making the most of the men's leisure time in camp. Among the most interesting hut activities were the lecture series, designed in the words of hut worker Sherwood Eddy for the 'recreational and mental employment' of the men. The Association funded leading scholars from British universities to tour the base camp huts, lecturing men on subjects as diverse as biology and theology. Eddy hailed the success of the program, claiming that it resembled 'the schedule of classes and lectures for some great university’. Some topics related directly to the war experience, such as Principal Ritchie from the University of Nottingham who lectured on 'European history and the Balkan situation', while others such as Professor Bateson of Cambridge, lectured more theoretically on academic disciplines (in Bateson's case: biological science). Senior clergy also advanced the YMCA's religious mission in lecturing on the Bible and preaching the story of Israel.

At least in the reckoning of the hut workers, these lectures seemed to have been popular with the troops. However, they were seen less positively by General Rawlinson, who told YMCA worker Barclay Baron that this sort of knowledge was superfluous and that ‘all you need to tell the men is – beat the

Boche’! He thought that teaching the men too many things would distract them from their primary purpose of being good soldiers and overcomplicate their minds. However, his protestations went ignored by the YMCA, who pressed on with their lectures in the base camps like those at Etaples. Baron remained in support of his Association's work, despite the resultant severance in his relationship with Rawlinson.

More popular with the high command, were the musical concerts hosted in the huts during the evenings. The YMCA prohibited the sale of alcohol in their huts and thus, the hut environment was seen as a wholesome alternative to the estaminets and bars outside of the camp. Not only would this promote temperance among the soldiers, but also prevent them from becoming tempted by French prostitutes. As of 1917, there were three Lena Ashwell Concert Parties constantly touring the base camps of northern France, two of which regularly visited Etaples, performing up to three concerts per day. Lena Ashwell herself was a popular London entertainer who had gone to the Western Front as part of an experiment in February 1915 to find suitable entertainments for the troops. She was immediately met with a 'rapturous welcome', with the soldiers enjoying the popular songs performed by the parties. Ivor Novello was among those who performed in the huts, and his song 'Keep the Home Fires Burning' quickly became a hit for the soldiers. For the YMCA, these concerts were important not only for raising the morale of the soldiers, but also for increasing their audience, with many non-religious men being drawn to the huts on the good reputation of the concerts. One such soldier, a Private R Cude, recorded in his private memoir that although he had little time for religion in his life, he found the YMCA's concerts to be 'extremely good'. Therefore, unwittingly or otherwise, he had been exposed to the Christian morality which pervaded the YMCA's actions through the Association's provision of secular entertainments.

While the YMCA operated from a 'spiritual basis', as described by hut worker Rev. Basil Bourchier, in which 'the spectacle of faith [was] related to life', the priority of most of the YMCA's activities in base camps such as Etaples was to boost the morale of the soldiers. One way to achieve this was through special celebration days, such as the festivities organised for ANZAC Day in 1917. YMCA worker Betty Stevenson described how the Association had organised 'sports and football' in the Canada Park area, with a temporary YMCA tent providing free refreshments throughout. She viewed the day to be a big success, attended by 'the biggest crowd of ANZACs, Australians and New Zealanders that I have ever seen'. Sports and games were a particular proclivity of the YMCA as they supported the competitive, boisterous and active characteristics that were deemed to make good soldiers, while also being good fun. Thousands of footballs and cricket sets were sent out to the huts throughout the war, paid for by donations. Board games and dominoes were also enjoyed within the huts, although cards were discouraged for fear of gambling.

Among the soldiers to have enjoyed the YMCA's hospitality at Etaples was the poet Wilfred Owen. Hut worker Conal O'Riordan remembered Owen with fondness, writing that he came to the hut 'almost every day' during his stay at the camp in September 1918, 'smiling at me in the sunlight or under the rays of the swinging lamp' upon his arrival. By many soldiers, the YMCA hut, symbolised by its 'Red Triangle' emblem, was seen as a place of relaxation and comfort; a routine place to visit for a cup of British tea and a biscuit. This environment, which reassured soldiers and reminded them of home, was the product of the Association's caring and dedicated staff. A number of these were religious men too old or unfit to fight, but significantly they were also clergymen, like Rev. Bourchier, who had opted against taking a chaplains' commission, and 40% were also women, often from the middle classes. Jeffrey Reznick has identified that female workers were presented as 'mothers' and 'sisters' in the huts: domestic, caring roles that were deliberately non-sexual.

One such lady was Betty Stevenson, a 20 year old from Harrogate, who worked as a driver for the YMCA in the Etaples area. Her story is a poignant reminder that although the base camps were built at a perceived safe distance from the front line, they were nonetheless operating in a dangerous war zone. Stevenson was killed by a bomb from an air raid on 30th May 1918. Since the German Spring Offensive Etaples had come under threat from air raids and while precautions were taken, Stevenson was returning from a train station with a group of other workers when a raid came overhead. The ladies hid under a bank near the roadside and the raid appeared to be finishing when a plane disposed of several bombs near where the ladies were sheltering. One of them killed Stevenson, injuring two others. She was buried in the military cemetery at Etaples, the solemnity of which she had remarked upon in her letters home. She received full military honours at her funeral and was posthumously awarded the croix de guerre: symbols of the significance of the YMCA's wartime service.

Such was the impact of the YMCA, who forged themselves a place in the hearts and minds of the British nation through their support for the war effort. The comfort and entertainment provided by the Association, particularly in base camps like Etaples, became cherished by soldiers and came to impress commanders such as Field Marshal Haig and Lord Derby. The simultaneous provision of recreation, refreshment and entertainment - not to mention religion - meant that there was something for almost everyone, through which morale could be supported, inquiring minds educated, and most significantly non-religious souls introduced to the Christian ethos and morality. Etaples was not without its problems, as most evocatively demonstrated in the 1917 mutinies, but the YMCA was able to support soldiers through both the strains and monotony of war service alike.

Kathryn

This article is adapted from research included in my MA dissertation about the YMCA's support for the Churches in the First World War.

Sources

Ashwell, Lena, ‘Concerts at the Front’, in Told in the Huts: The YMCA Gift Book, (New York: Frederick A Stokes Company, 1916)

Baron, Barclay, ‘Memoirs’, in Snape, Michael (ed.), The Back Parts of War, (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2009)

Bourchier, Basil, ‘The Red Triangle from a Clerical View-Point’, Red Triangle Papers: The British Empire YMCA Weekly 93 (2) (20/10/1916), reprinted from The Church Times, Cadbury Research Library

Cude, R, unpublished memoir, Imperial War Museum

Culpitt, George, war diary, http://www.culpitt-war-diary.org.uk/CH_02.htm

Eddy, Sherwood, With our Soldiers in France, (New York: Association Press, 1917)

Guest, Philip, Wilfred Owen: On the Trail of the Poets of the Great War, (Barnsley: Pen and Sword Books, 2013)

Stevenson, Betty, http://www.yretired.co.uk/Betty%20Stevenson%20-%20YMCA%20Women%27s%20Auxiliary%20-%20THE%20HAPPY%20WARRIOR.pdf

Reznick, Jeffrey, Healing the Nations: Soldiers and the Culture of Caregiving in Britain during the Great War, (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2004).

Winter, Thomas, ‘The Diary of a YMCA Worker’, unpublished manuscript, Cadbury Research Library

|

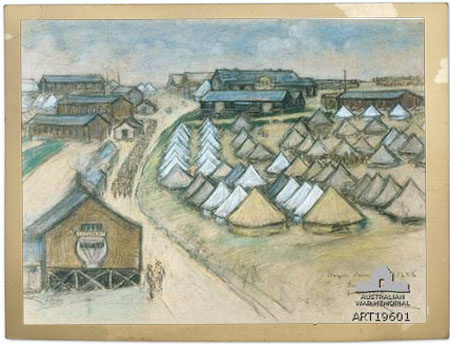

| 'Troops Arriving at ANZAC Camp', by Iso Rae (source) |

Thomas Winter was among the YMCA's workers based at the camp. He wrote of the huts' provisions which exceeded the regular provision of refreshments and light entertainment to include concerts, lectures, weekly Bible study and free French lessons; making the most of the men's leisure time in camp. Among the most interesting hut activities were the lecture series, designed in the words of hut worker Sherwood Eddy for the 'recreational and mental employment' of the men. The Association funded leading scholars from British universities to tour the base camp huts, lecturing men on subjects as diverse as biology and theology. Eddy hailed the success of the program, claiming that it resembled 'the schedule of classes and lectures for some great university’. Some topics related directly to the war experience, such as Principal Ritchie from the University of Nottingham who lectured on 'European history and the Balkan situation', while others such as Professor Bateson of Cambridge, lectured more theoretically on academic disciplines (in Bateson's case: biological science). Senior clergy also advanced the YMCA's religious mission in lecturing on the Bible and preaching the story of Israel.

| A New Zealand YMCA Hut at Etaples, 1918 (source) |

|

| 'The Great Push', Bert Wardle (source) |

| A sketch of a YMCA hut sponsored and staffed by the Scouts Association (source) |

Among the soldiers to have enjoyed the YMCA's hospitality at Etaples was the poet Wilfred Owen. Hut worker Conal O'Riordan remembered Owen with fondness, writing that he came to the hut 'almost every day' during his stay at the camp in September 1918, 'smiling at me in the sunlight or under the rays of the swinging lamp' upon his arrival. By many soldiers, the YMCA hut, symbolised by its 'Red Triangle' emblem, was seen as a place of relaxation and comfort; a routine place to visit for a cup of British tea and a biscuit. This environment, which reassured soldiers and reminded them of home, was the product of the Association's caring and dedicated staff. A number of these were religious men too old or unfit to fight, but significantly they were also clergymen, like Rev. Bourchier, who had opted against taking a chaplains' commission, and 40% were also women, often from the middle classes. Jeffrey Reznick has identified that female workers were presented as 'mothers' and 'sisters' in the huts: domestic, caring roles that were deliberately non-sexual.

| Betty Stevenson (IWM) |

Such was the impact of the YMCA, who forged themselves a place in the hearts and minds of the British nation through their support for the war effort. The comfort and entertainment provided by the Association, particularly in base camps like Etaples, became cherished by soldiers and came to impress commanders such as Field Marshal Haig and Lord Derby. The simultaneous provision of recreation, refreshment and entertainment - not to mention religion - meant that there was something for almost everyone, through which morale could be supported, inquiring minds educated, and most significantly non-religious souls introduced to the Christian ethos and morality. Etaples was not without its problems, as most evocatively demonstrated in the 1917 mutinies, but the YMCA was able to support soldiers through both the strains and monotony of war service alike.

Kathryn

This article is adapted from research included in my MA dissertation about the YMCA's support for the Churches in the First World War.

Sources

Ashwell, Lena, ‘Concerts at the Front’, in Told in the Huts: The YMCA Gift Book, (New York: Frederick A Stokes Company, 1916)

Baron, Barclay, ‘Memoirs’, in Snape, Michael (ed.), The Back Parts of War, (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2009)

Bourchier, Basil, ‘The Red Triangle from a Clerical View-Point’, Red Triangle Papers: The British Empire YMCA Weekly 93 (2) (20/10/1916), reprinted from The Church Times, Cadbury Research Library

Cude, R, unpublished memoir, Imperial War Museum

Culpitt, George, war diary, http://www.culpitt-war-diary.org.uk/CH_02.htm

Eddy, Sherwood, With our Soldiers in France, (New York: Association Press, 1917)

Guest, Philip, Wilfred Owen: On the Trail of the Poets of the Great War, (Barnsley: Pen and Sword Books, 2013)

Stevenson, Betty, http://www.yretired.co.uk/Betty%20Stevenson%20-%20YMCA%20Women%27s%20Auxiliary%20-%20THE%20HAPPY%20WARRIOR.pdf

Reznick, Jeffrey, Healing the Nations: Soldiers and the Culture of Caregiving in Britain during the Great War, (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2004).

Winter, Thomas, ‘The Diary of a YMCA Worker’, unpublished manuscript, Cadbury Research Library

Thank you ffor this

ReplyDeletemain yang pasti pasti gacor aja

ReplyDeleteyuk main kan game seru nya sekarang!!

wa: +62 877-6009-5191