Recruitment in Manchester: 1914-15

| Men wait to enlist in a wet Manchester (photo source) |

Following the declaration of war in August 1914, there was a great movement to encourage

men to volunteer for military service across the country. The British Army available for

deployment to Belgium in 1914 numbered only 82,000 men and they could not hope to present a strong force against the much larger and more organised Germans. Lord Kitchener, the Secretary of State for War, led the drive

for the voluntary recruitment of 600,000 men to form his New Army to supplement the

pre-war professional soldiers of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF). At the time, approximately 1.7% of the

British population lived in the city of Manchester (based on 1911 census

statistics and national population data), so in a statistical sense, Manchester

had to aim to recruit 10,200 volunteer soldiers.

|

| Recruitment thermometer, Town Hall |

Patriotic fervour soon swept the nation and dominated the

press. In the first days men queued for hours to enlist, with Manchester men

going to the Ardwick Artillery Barracks and Manchester Town Hall to volunteer.

In Ardwick, the queue stretched out for a mile and the Town Hall became so

overrun that the nearby Albert Hall also had to be set up as an enlistment

station. On the outside walls of the Town Hall ‘recruitment

thermometers’ were displayed to show the city's progress. The photo on the left shows the recruitment for 20th (5th City) Battalion of the Manchester Regiment, who achieved

their aim of 1,070 men recruited from civilians in less than 48 hours. The poster next to it promises men that they can serve with their 'pals'. Spirits were high: no sense of the following five years of bloody stalemate was known and was much less communicated to the public.

| GL Jessop in Albert Square (photo source) |

Many men, particularly young groups of friends, had been keen to enlist both on the basis of 'doing their "bit" for King and country' and as it was seen to be an exciting adventure. However, others were more reluctant, understandably not wanting to leave behind the relative safety of the city. In order to encourage men to enlist and to inspire

patriotism in the population, recruitment rallies were held. These continued after the immediate wave of recruitment after the Autumn of 1914, with one such meeting being led by the legendary Gloucestershire cricketer Gilbert L Jessop in Albert

Square, outside the Town Hall, in April 1915 (see photo, right). Although he had retired from

sport, he served as a Captain in the Manchester Regiment and the army utilised

his fame to promote recruitment before he saw active service. Such rallies were

often crowded and gave a lot of the impetus into the recruitment drives.

|

| The King Street District Bank Roll of Honour (photo source) |

For many men, particularly those who were young and

unmarried, the pressure to enlist came from many directions. In addition to the

recruitment drives and rallies, posters were appearing all over the city. Men

were ‘expected’ to enlist and to ‘play their part’ for the nation. For many,

pressure also came from employers who sent their workers enlist together,

honouring those who did on a Roll of Honour. The Co-operative and the

District Bank (now part of RBS, see above photo) were among employers to take

part. Many of these men would have been office clerks, who were among the white collar workers targeted in Kitchener's recruitment drive. It was believed that these lower middle class men would perform well in the discipline and rigour of the army. It was also easier for their jobs to be taken over by older men, unsuitable for military service, and even women later in the war.

|

| Recruitment poster (photo source) |

In the early days of the war, when recruitment campaigns

were at their most fervent, most men who enlisted together would serve

together. These were the ‘pals battalions’, thought by Lord

Derby to encourage men to fight as they would have the camaraderie of friends

with them at the front. The scheme was a disaster, with

communities being decimated of men in single battles.

Nonetheless, it could certainly be seen as an encouragement to those who joined

up together and who were seen to be enjoying the early days of training with

friends. One of the notable pals battalions was the Football Battalion (formally the 17th Battalion, Middlesex), which was composed of many professional footballers, including Manchester United professionals Billy Booth and Oscar Linkson.

|

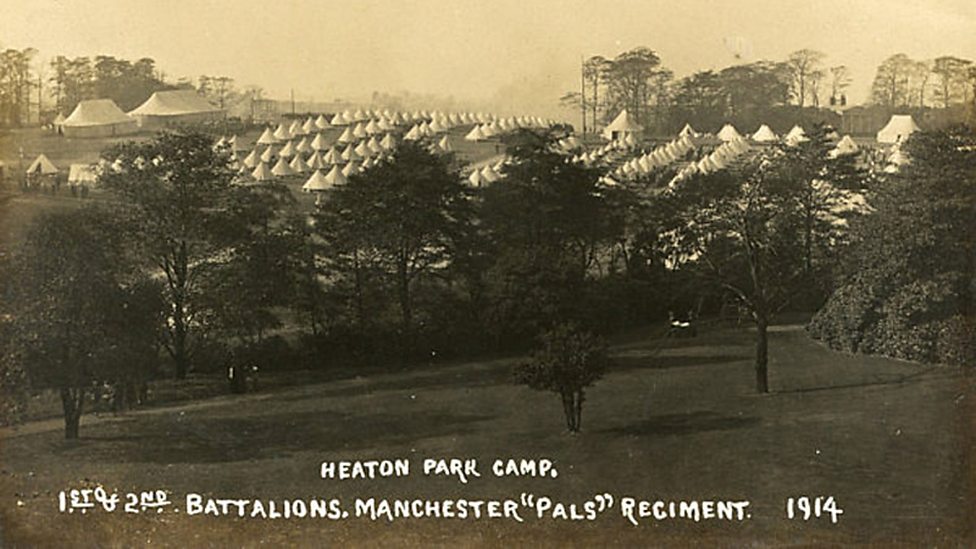

| The training camp at Heaton Park (photo source) |

The Manchester Regiment raised a total of eight city battalions in the latter months of 1914 to support the regular and

territorials armies, with each numbering approximately 1,000 men. There were a further

five battalions formed in Ashton-under-Lyne and Oldham. Rudimentary training

began almost straight away, although progress was initially stalled by a lack

of funding for housing and dressing the new troops, or for equipment and

weapons. A huge tented village was erected in Heaton Park which could accommodate

5,000 troops for six months of basic training. Here, they learnt all aspects of

army life despite many of them being hampered in the early days by a lack of

weapons. In some cases broom handles even had to be used in place of rifles,

with the numbers of soldiers in the army expanding at a much faster rate than

the government was able to procure and distribute weapons.

|

| Trainee soldiers in blue uniforms learn trench construction |

Much of the training equipment had to be privately funded and Manchester responded to the challenge, with Joseph O'Neill noting that the people of Manchester raised £165,568 for the cause by the end of 1914. Equipment was slowly received, although compromises had to be made. Running low on the green-grey khaki fabric from which uniforms were made, many of the new recruits were given blue-grey uniforms in lieu. These were resented by some Manchester men as they resembled the uniforms worn by workers on the city's tram service. Boots were also a problem, with limited stocks meaning that some men received ill-fitting ones which would cause them much pain in their physical training. However, for some, this was a time of great opportunity and excitement. Many of the working class recruits relished being able to wear high quality leather boots.

Lord Kitchener (in centre, on steps) inspects the Manchester troops, 1915

Manchester was praised for its recruitment, and on 21st March, 1915 Lord Kitchener himself came to the city where he inspected 11,000 men from the local troops on the steps of the Town Hall (see above photo). These men were already local heroes, but their war had barely yet begun. The battalions would complete their training in various locations within England, before sailing for France in the final months of 1915. They would then spend several months in the trenches of the Somme region and completing further training before they would enter their first major battle on the First of July 1916... The rest, they say, is history.

Kathryn

Bibliography:

Joseph O'Neill, 'Manchester in the Great War'

Chris Makepeace, 'A Century of Manchester' (all uncredited photos above come from this book)

The Manchester Regiment, www.themanchesters.org

No comments: